The Notebook and MOTHER 3

by: Kody NOKOLO on 8/4/2020

Le Grand Cahier, known in English as The Notebook, is the first in a set of three novels written by Hungarian author Ágota Kristóf. Back when MOTHER 3 was still slated for release on the Nintendo 64, creator Shigesato Itoi revealed that the names of the game’s twin brothers, Lucas and Claus, were inspired by the twin narrators of the same name from Kristóf’s story. This is just one of many parallels to the game though — factoring in every similarity, it’s easy to see the heavy influence this series had on Itoi when he first wrote the game’s script!

The Notebook begins with Lucas and Claus, made to live with their abusive grandmother in a border town to survive the war, as their mother can no longer support the two of them. Living conditions in their new home are vile: The children are left unbathed and barefoot as the grandmother sells their belongings. Even the townsfolk see the boys as scoundrels, not hesitating in physically and verbally abusing them. In order to adapt to this cruel environment, the twins vow to toughen themselves up via “exercises” of the body. They whip each other with belts to normalize pain, starve themselves to “conquer” hunger, and practice inflicting cruelty by murdering innocent creatures. In an effort to become truly stoic, their “exercise of the mind” involves repeating words and phrases their mom lovingly used to tell them until the meaning and sentiment is gone. Statements that make the twins tear up to remember have become too painful to bear, so they repress their mother’s memory, just as Claus is forced to do as the Masked Man at the beginning of MOTHER 3’s final battle.

The twins’ record all their experiences and routines in the namesake “notebook,” with each entry presented as a separate chapter. Its purpose is to document precisely what happens as matter-of-fact, so they forbid defining feelings and using language like “love” because it isn’t a reliable, objective word. Like MOTHER 3, whose characters rarely emote, it’s up to us to “fill in the blanks” as to the characters’ emotional state throughout these stories. The structure of the novel and the boys intense training is probably what Itoi was referring to when he compared the book to an RPG: the children acclimating to pain and “leveling up” by hardening themselves.

Itoi has stated that a fundamental theme of MOTHER 3 is welcoming those that may be dismissed otherwise. Duster, for example is a strong, invaluable party member that was included in the game because Itoi wanted to portray a character “with bad breath, a disabled leg, and living as a thief”. Having friends like Duster, then, became “symbols of not rejecting such people”. It’s an idea seen in many aspects of this first book, such as Harelip; a tragic girl described as cross-eyed, with blackened teeth and pimples covering her body. Her mother is immobile, so Harelip has to care for herself by swiping food from town. When she steals from the boys’ farm, they don’t scoff at her appearance or chase her away, recognizing instead a person looking out for her family. They befriend the girl because of her good intentions.

Midway through the first book, a perverse bathing scene occurs in which the priest’s housekeeper sexually engages the twins. In MOTHER 3, nothing offensive actually happens between Lucas and Ionia during his hot spring awakening, but Itoi purposefully crafted that sequence from the perspective of an adult, to make young players “nervous and confused about what was going on in the hot spring in that tunnel…”. The dialogue is intentionally suggestive to raise questions, even if what truly occurs isn’t obscene.

In both the game and novel, the twins’ mother dies gruesomely in front of them. In MOTHER 3, the boys’ mother is killed violently when a once-friendly creature pierces her heart, while in The Notebook, a bombshell explosion kills their mother and newborn sister. In MOTHER 3, this is THE event that changes everything. A sadness in Hinawa’s abrupt murder permeates throughout the rest of the story and especially impacts the twins. In The Notebook however, their mom’s sudden death happens towards the end — by which point they’re so desensitized to trauma that the event leaves them rather unphased. Lucas and Claus’ mother being caught in an explosion may have also been the intended way for Hinawa to die in MOTHER 3, as evidenced by a related, unused cutscene found within the game’s data.

Another major parallel in both stories is the communal effect of military occupation. Upon enemy victory in The Notebook, their so-called Liberators ravage the village before occupying the country, developing the town to their vision in a similar vein to the Pigmask’s reform of Tazmily Village. Tazmily turns from a place without need of regulation to being heavily officiated by a violent police force, threatening and punishing those not loyal to the new army. Pigmasks, to a certain capacity (eg. their “salute”) resemble Nazi soldiers too, i.e. the opposition in Kristóf’s story.

When their father returns from the front in The Notebook, he talks about needing to flee the country for his own safety, since he’s targeted for being “politically suspect.” As a chance for escape, he doesn’t care if he dies trying to cross the border’s landmines, even though at this point in the story he’s the only family the boys have left. Absent father figures are present in every game of the MOTHER series, but MOTHER 3’s Flint (while arguably some degree of insane after his wife’s death) similarly chooses to leave Lucas behind.

The Notebook ends with one last exercise for the twins: Separation. After their father attempts to cross the border first (which detonates a landmine, killing him), Claus steps across his father’s corpse and over the fence, while Lucas stays behind. MOTHER 3’s twins were forced into splitting apart, but in the novel they choose to part ways as a final test of will.

The Proof (The Notebook’s sequel novel) picks up from the perspective of Lucas, who is now referred to as the “village idiot,” because of his nervous disorder from the trauma he suffered during the war that ended five years ago. He is an outcast living alone and unsure how to function without his brother by his side. He can’t eat, is afraid to go into his and Claus’ old room, and neglects the garden because his memory fails him. His mental deterioration is reminiscent of Flint’s obsession with finding his missing son to the point of omitting responsibility. The Proof’s Lucas being shunned by his hometown reminds us of that same dynamic in MOTHER 3’s Lucas too; the boy is labeled a crybaby by his peers, and is disdained from Chapter 4 onward for rejecting Tazmily’s Pigmask influence by not accepting a Happy Box.

The Proof’s Lucas eventually stumbles upon a woman trying to drown her baby, but can’t go through with it. He takes the both of them in and later adopts the deformed child (named Mathias), crippled because his mother tried to hide the fact she was pregnant by wearing a tight corset. His legs specifically are disabled, which could be (like Harelip, the thief and ally from the first book) an inspiration for Duster. There are a couple of lines in the game that suggest Duster has his limp because of a training accident, under his father’s strict discipline. Lucas similarly pushes Mathias too hard but in an opposite way: to correct his legs so that he can stand upright and “walk like everyone else”. Much like Wess though, who expects too much from his son, Lucas loves Mathias and wants the very best for him, believing his method of parenting to be what the child needs to grow.

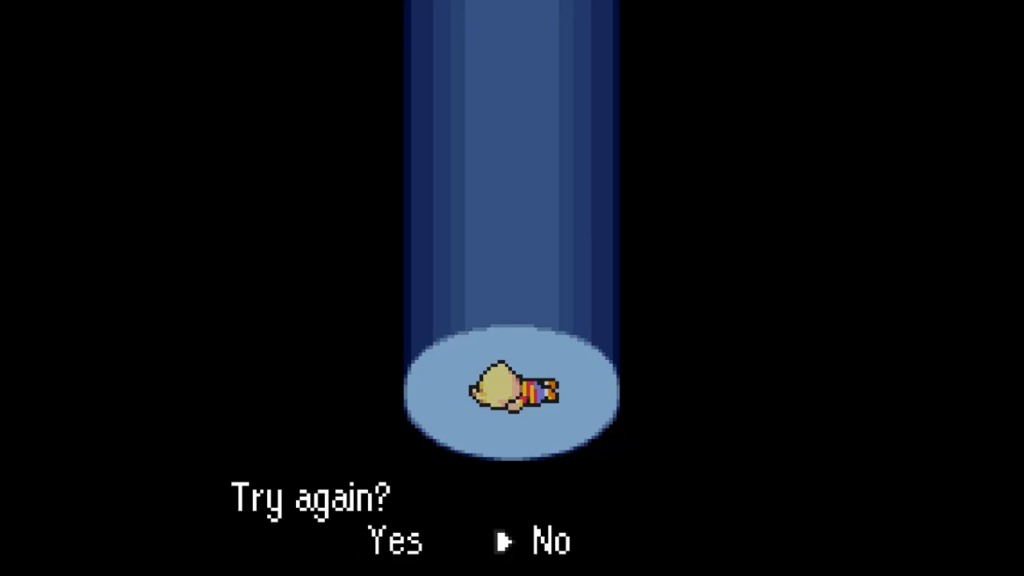

When Mathias’ mother leaves him and Lucas for “the big city,” the child is convinced she did so because he’s crippled. Mathias is riddled with trust issues, insisting Lucas will leave him at an orphanage, which results in vivid recurring nightmares about losing his family. This likely resonated strongly with Itoi, because they share a similar mindset: “If I had to say what my worst kind of nightmare might be, it would involve my friends and family all being evil”. This psychological torment is brought to life by the hallucinations with Wess, Claus, and Flint on Tanetane Island.

Disturbingly, the fear and despair in loneliness causes the 7 year-old Mathias to hang himself. This, of course, utterly defeats Lucas. He slumps into a worsened depression and no longer speaks, sleeping on the child’s grave every night. Years pass like this, and at age thirty Lucas finally disappears from town. The end of the story transitions twenty more years from that moment to the perspective of a fifty year-old Claus, arriving by train in search of his brother.

The book concludes with Claus being taken into custody, having waited for his brother with an expired visa extension and invalided ID. The authorities are not able to verify any record of Lucas or Claus living in town, and reveal the notebook Lucas has been adding to since the first novel to likely be a work of fiction. This trippy ending sequence implies that all of what happened throughout these last two books are fabrications. With such a surprising revelation, it’s as if the author wanted to betray the reader, since everything so far has been presented as fact while it was happening. Itoi revealed a similar desire to “betray the player”, when he explained that EarthBound 64’s scenario had planned to “dig in the direction that would upset people”. While Itoi could be referring to anything narratively, a plot twist we did get that changes everything in MOTHER 3 is found during Leder’s speech towards the end of the game — all of Tazmily’s residents are memory-wiped survivors of a world-ending apocalypse, living their new lives as blissful lies!

The Third Lie (the last book in the trilogy) elaborates that it wasn’t actually a fifty-year-old Claus who came back to his hometown and was arrested. Well, it was — but Claus (as we’ve known him throughout these two stories) doesn’t really exist. Claus is an alias Lucas has been using when he alone crossed the border all those years ago. Mixing up twins is a common trope in any kind of media, but in both Itoi’s and Kristof’s tale, it is crucial for the sake of storytelling that these characters are twins so that their identities are easily swappable.

Lucas confides during his arrest that he did write his manuscript as an embellished autobiography, and that he tries to write using facts but “at a given point, the story becomes so unbearable because of its very truth” that he has to change it; “It hurts too much”. Lucas chose the assumed name of Claus with a “C” (an anagram of his own name) in memory of his actual brother, Klaus with a “K”. The twins were separated at the age of four, not fifteen, due to an event dubbed “the thing”, as in “the thing” that ruined all of their lives. At this terribly young age, the boys’ father admitted to their mom that he was having an affair, which resulted in his wife shooting and killing him with his own revolver. One of the bullets ricocheted into Lucas’ leg, crippling him, so he was sent away to be hospitalized. Klaus (with a K) was made to live with his dad’s lover, while their mom was transferred to a psychiatric ward, having become clinically insane, believing she killed Lucas. During his years spent in the hospital not receiving any word from his family, Lucas became bitter, lashing out at the staff and bullying his fellow patients. While only a character he imagined for the manuscript, it becomes obvious that Mathias was meant to represent Lucas as a child. Lucas was always the one with a deformed leg, believing that everyone’s families hate them because of their disabilities; just like Mathias’s greatest fear, and the very reason for killing himself in The Proof.

Their mother didn’t actually die from a shell landing in their garden like in The Notebook either; it was instead Lucas’ hospital that was bombed from the war. This forced him to relocate, to live with a mean peasant woman he learned to call “grandmother.” Of course, when Lucas decided to cross the border then, it wasn’t his father he made go first. It was a willing stranger Lucas only claimed to be his dad as a convincing story for when he made it to the other side. It is in this country that Lucas (claiming to be an adult of eighteen) assumed the name Claus with a “C”. Three mistruths so that he wouldn’t be sent back; his alias is the third lie.

It is a sick, dying Lucas at age fifty who returns and is imprisoned in town looking for his brother Klaus. When he finally does find and meet with his brother in the capital, the encounter is anything but wholesome. Like protagonists changing in MOTHER 3’s chapters, the book shifts one last time to Klaus’ point of view, painting the tale of a miserable man who’s wasted away his life (and health) working at a printing press. The dramatic irony of Flint just barely missing his son in MOTHER 3 is mirrored when Klaus is forced to temporarily move to the same town as his brother because of the war. He sees Lucas performing at bars, but doesn’t recognize him. As an adult, Klaus dedicates himself to taking care of his mother in their childhood home where “the thing” happened, and he hasn’t left her side since. The problem, though, is that their mom never mentally recovered. She still insists that Lucas died by her hand, chastising Klaus for being the “lesser” twin. Her vision of Lucas is of a perfect child, and Klaus is reproached in every way. It’s an obsession with just one of her sons that (again) hearkens back to Flint leaving Lucas behind to compulsively search for his Claus. Because of this toxic relationship, Klaus slowly begins to despise the brother he never got to know. So after forty-six years, when the twins are finally reunited, Klaus shuts Lucas out completely.

Like Lucas did in his manuscript, Klaus lies about his life, claiming their mom really is dead and fabricates his story as one he wishes were true — much like the self-brainwashed residents of Tazmily living their “ideal roles” while hiding the truth. He rejects Lucas as his brother, because of a lifetime of spite developed from an awful mother. Lucas leaves dejectedly, and jumps in front of a moving train, killing himself. The book series ends with Klaus watching his brother’s coffin being lowered next to their father’s grave, thinking that the four of them will be reunited soon (much like Claus’s last sentiment in MOTHER 3, following his suicide). When their mom passes away, Klaus will have no reason to go on, so the final sentence has him stating: “Not a bad idea, the train”. As Itoi was inspired by the twins’ bond in The Notebook, it’s very likely their separation through a timeskip and this tragic theme of never truly being able to reunite again strongly influenced Itoi as well. Claus’ death in MOTHER 3 may very well have been a reflection of Klaus’ plan for suicide (and Lucas’s actual suicide) in The Third Lie. Lucas putting himself in danger by crossing the train tracks in MOTHER 3 is given a lot of attention, too. If the player tries to enter the train tunnel before progressing the story, a man and his twin brother from the other side of the tracks will pull Lucas aside — saving his life — an action that can be repeated again and again for new dialogue. The pair of them will scold Lucas in different ways, telling him not to throw his life away. Paired with the fact that there’s real risk in Lucas getting hit by the train, it’s a bit disturbing now given the context of Itoi’s inspiration!

Page Contributors

Thane Gaming – Writer

8lackSphinx – Editor

Find any errors or want to contribute? Let us know in our Discord!