Octopi! Spinal Tap! How Cult RPG EarthBound Came to America

by: Echoes on 4/28/2020

Spend a few minutes perusing the mountains of fan art, videos and tributes on fan sites like EarthBound Central or Starmen.net, and you’ll see that the classic role-playing game Earthbound has an extremely dedicated fan base. Which is surprising, considering Nintendo never sold many copies of it.

Translated from the Japanese game Mother 2 and released on the Super Nintendo in June 1995, EarthBound had a lot of things going against it. Role-playing games weren’t very popular in the U.S. yet, and those few RPG players who did exist were content with flashier games like Chrono Trigger or Final Fantasy VI. It carried a $70 price tag thanks to Nintendo’s decision to include a large-format strategy guide with the game in order to help players navigate its wacky, unpredictable storyline.

All told, Nintendo sold less than 150,000 copies of Earthbound. Those players who did take the plunge found a game full of endearing characters, ridiculous jokes and bizarre situations written by popular Japanese writer Shigesato Itoi. As with all cult classics, EarthBound’s reputation took a while to develop. Today, you have to spend upwards of $150 to buy an original cartridge on eBay (and much more if you want the strategy guide and box).

Last week, Nintendo finally re-released EarthBound for the first time, as a $10 download for the Wii U console. To mark the occasion, WIRED caught up with Marcus Lindblom, who translated and re-wrote the game’s text from Japanese to English. It wasn’t just a simple translation job – since the original was filled with Japan-specific puns and gags, Lindblom had to do a lot of writing and creative reworking, eventually putting his own creative stamp on EarthBound.

WIRED: How did you feel when EarthBound was first released and didn’t sell well?

Marcus Lindblom: The sales were definitely disappointing. But I wasn’t really surprised for a couple of reasons. The first thing was the price of the game. By including the strategy guide in the box, which I felt was a great guide and one I’m very happy with, the cost of the game needed to be higher. For a game that hadn’t established an audience, it was an expensive proposition for lots of gamers.

The second issue, which became apparent when the reviews started to come in, was the graphics. In those days of the Super NES and the Sega Genesis, sophisticated graphics were becoming a key feature, as Sega emphasized the speed of the Sonic the Hedgehog games, and Nintendo followed with “Mode 7” graphics and the Super FX chip, used in games like Star Fox to render 3-D visuals.

To many of the reviewers at the time, EarthBound’s graphics looked like enhanced 8-bit graphics, and felt a bit too much like a throwback that the market wasn’t looking for yet. Ironically, the aesthetics seem to play very well today in this age of retro gaming. The cuteness, colors and hallucinatory bits are called out as favorites by lots of fans these days. But back at the time of release in 1995, this certainly wasn’t the case.

So it was disappointing, especially after working really hard during a short development window, to see the game under-perform. I was, at least, personally and professionally satisfied that the reviewers acknowledged the game’s sense of humor. That helped take some of the sting out of the sales figures, but nothing could change the fact that the game was viewed as a “miss” within the company.

Wired: Could you talk about some of the difficulties you had in localizing EarthBound?

Lindblom: The biggest challenge we had in a lot of ways was how to handle the cultural references.

The thing that’s really weird about Earthbound is that I was trying to translate someone’s view of what the U.S. is like from the outside — someone who, obviously, isn’t American. I had to take an outsider’s view of the U.S. and turn it into something everybody here would play and understand. That was one of the more difficult things to do.

We had to take out references to alcohol. Everything in the English version is coffee-based.The other thing we did try to do — and we weren’t always 100 percent successful — was tone down a lot of the references to intellectual property. I didn’t really do anything with the music. The music was actually already pretty much done. But when it came to visual or textual references, we did definitely look at it and say “Okay, the artwork on the truck looks a little bit too much like the Coca-Cola logo, we need to change that.”

Then we had to take out the red crosses on the hospitals because we knew that was sort of questionable even at that time. They could come and say, you know, because there’s the actual organization The Red Cross who uses that as their symbol.

Wired: So that specifically was not Nintendo coming in with their censorship policies and saying “Well, you can’t have anything resembling a cross”?

Lindblom: (laughs) Well, actually, that is true. They wanted as few religious references as possible, no matter how seemingly innocuous.

Although we did leave the word “pray” in the game just because we thought that was kind of nice and general enough that it didn’t necessarily feel, to me at least, that I had to take that word out. Because honestly, I really didn’t want to put the word “wish” in or something like that because that just sounded lame to me.

But yeah, religious stuff, yeah they definitely had a policy that said we needed to take all of that out, we needed to take out things that were questionable in regards to, like I said, intellectual property.

We did actually miss a cross on a tombstone. There was so much stuff in the game that had to be reworked or touched up in terms of visuals, so I wasn’t terribly surprised they missed one little tombstone.

But they did a good job. They really went through and combed and took out all kinds of little references. We had to take out all the references to alcohol, too. So that’s why everything in the English version became coffee-based.

Wired: I think the coffee instead of alcohol is a lot funnier, honestly.

Lindblom: Well, it was quirkier, right? The one really great thing, for me, about working on the game was when they approached me about working on it, they did say “Don’t worry about making things a little strange.” Because, you know, the game is based on some pretty strange things.

It gave me a lot of license to be as weird as I wanted to be and I certainly took advantage of that in a lot of places. But I also wanted to stay as close to the original Japanese work as possible.

So I had three goals: Stay true to Mr. Itoi’s writing because, well, it is great writing with a fantastic story and there’s just a lot of heart and a lot of great things in there. At the same time, I didn’t want to have a really disjointed, confusing story because, you know, I had seen a lot of bad translation work that just didn’t work well at all. Then the last thing was I really did want to keep the game in that goofy, quirky sort of vein as much as I could while staying true to the first two things.

Luckily, I guess I must have achieved something with it because most people seem to respond well to the work.

It wasn’t easy, though. We had to go back and forth and figure out what would be the best thing to do in some of the stranger situations in the game.

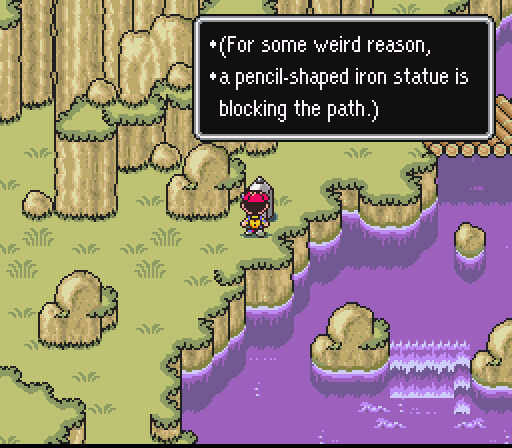

For example, you know the part in the game where there’s an iron pencil and eraser statue blocking your path and you need to get an item called the “pencil eraser” and the “eraser eraser” to progress? In the original Japanese version the pencil was an octopus and the eraser was a Japanese kokeshi doll.

So those two objects, I knew just wouldn’t play in the U.S. I mean I couldn’t do an octopus because people here don’t really care about octopi (laughs). Whereas they’re really important in Japan and they’re this… You know there’s a group of people in Japan where octopus and sealife is a big deal in their life and culture.

Then the kokeshi doll was more of a play on words in Japanese because the word keshi means to erase. So Mr. Itoi did this clever pun in the Japanese game where you get an item called the kokeshi keshi.

So when I was trying to figure out how to handle that, the guy from Japan was like, “I have no idea what you want to do here. You can make it weird if you want.”

Then I said “Well, there needs to be something that’s an eraser,” and I thought “Well if the item is called the ‘pencil eraser’ then it’s kind of funny if there’s just a big metal pencil.” So that worked and then the next thing was like, okay let’s just call it the “eraser eraser.” Which ended up playing off the kokeshi keshi idea.

It worked out but that was one of those cases where I had to come up with something odd that didn’t really have all that much to do with the original Japanese.

Wired: So some of these situations turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

Lindblom: Yeah, they really did because we got to play around with those things and it certainly added to the overall quirkiness of the game.

There are so many little bits like that where we tried to fix all kinds of things from the Japanese version and make it better for English audiences. I think it worked out pretty well. A couple of times, it was a little bit weird but, you know.

The ones I really remember were the Happy Happyists, the blue cultists early in the game. People have speculated that they looked too much like Ku Klux Klan members. And I can go ahead and tell you absolutely that was the case (laughs). They really did look like Klan members to me. And they had “HH” on their head, which looked a little too close to a K because a lot of times, with really low-resolution fonts, a K and an H look really similar.

There was no way I could let that one go. So I had them take the letters off and they put a little snowball on the end of the hat for me just to make sure it was as far away from the Ku Klux Klan as possible.

Wired: How long did you have to work on the game?

Lindblom: Our timeline was super squished. The game was released on June 5 of 1995 and I didn’t really start working on it until January of that year. And a lot of the graphical changes weren’t being implemented until March or April. Because we had to make all the systems work with the fact that you could name your characters and such.

The downside was we didn’t get a good playable English version until really late. I can remember even in April, there was a point where the testing team could only play about half the game before it stopped working. It was well into May before we had a version that could be played to completion.

Wired: Was there ever a point where you couldn’t get a piece of writing to work in English and had to come up with something completely original?

Lindblom: That’s a good question. I can’t remember anything off the top of my head but when I was watching [a player streaming Earthbound] the other night, there was a moment where she read a billboard that said something like “There’s a weird guy going around reading the boards and saying ‘check-a-rooney!'” And it looked like she thought “check-a-rooney!” was funny.

I’m sure the original Japanese didn’t say anything like that. That was one of those cases where I got to go in and deviate from the source and put in something I thought was goofy and funny. There’s a lot of those places in the game where what they say in English doesn’t really adhere to the original text.

I’ll be honest, too: There were plenty of times where I read the Japanese and thought it was a little plain, so I spiced it up in English.

Wired: Did you ever have to consult with Mr. Itoi and ask if it was OK to change something?

Lindblom: No, actually, I never did. It was nice because it was a very accepting environment. The thing that did influence me to a degree was that I lived in Japan for four years in the late 80s. So I was really comfortable with and aware of a lot of things in Japanese culture. I had a goal of keeping as many things in as I could but there was not much time to get all the nuances. But even in Japanese, some of those subtleties were really hard to explain to other Japanese people. Because it was very intricately written in some ways.

But I think Itoi probably told the guys I worked with that if we had a choice between things, then just make it interesting.

Wired: So Mr. Itoi wasn’t really involved in the localization.

Lindblom: Nope. You know what, I never actually met him. Now he may have talked to Dan Owsen before I started on the translation work but I never did talk to Itoi myself.

Wired: What were some of the things that inspired you when translating EarthBound?

Lindblom: There are lots of little things in the game that I see now and I know exactly where they came from. Some of it is absolutely from my own youth and things I thought were funny as a kid. So if anybody out there plays the game and thinks “It seems like someone must have been a Bugs Bunny fan,” they would be absolutely right.

There are occasional bits of Benny Hill in there. He was a British comedian who was popular in the 70s. His show was really goofy and cleverly written slapstick humor that I really liked when I was 16 or 17. Some of that certainly shines through in the game.

There’s another line in the game that I know was inspired by This Is Spinal Tap. I don’t think I’ve ever told anyone this but there’s a billboard in the game’s first town, Onett. It says something about “don’t break the wind of change,” which was inspired by the really dumb album title they had in Spinal Tap called Break Like the Wind, which was so stupid. That was the inspiration for that billboard.

Some things in the game were actually just taken from the things we were saying in the office and thought were funny at the time. That’s a thread that runs throughout the whole game.

Wired: Is there a line you love that you don’t see being appreciated as much?

Lindblom: I’ve told this a story a number of times to a few people but one of the lines that meant a lot to me actually ended up getting me back into the EarthBound community.

I got to put my daughter’s name in the game. It was important for me because my daughter was born in the middle of my working on it. I took the day of her birth off work but then I worked the next 30 days straight. I didn’t get a weekend off, I didn’t do anything but work on the game because we were in crunch mode. I was coming home late but was able to feed her and put her to sleep.

It was a hardship on my wife, too, in some ways but they told me if I wanted to put my daughter’s name in the game, then well, go ahead. So there’s this little girl character very late in the game who isn’t really important. In English, she says “Hi, my name’s Nico,” which is the name of my daughter. The fact that they let me do that was a big deal and I was very happy. It was a very personal line for me.

But years later, I saw a few forum posts on the EarthBound community at Starmen.net asking about the Nico character and coming up with theories about her being Ness’ old girlfriend and such. It made me realize there were people out there who really cared about the game. For me, it was a line I had put in for purely personal reasons but people were reading into it and eventually it got to the point where I did finally tell people about my work on the game.

The fact that anybody out there saw that character and wondered why she was there meant a lot to me.

There have been a number of times where people have called out a line and I’ve realized it was a line I always intended to go back and fix but just never did. But even the fact that people saw those lines and cared enough to mention them really does mean something to me.

Wired: Can you talk more about what EarthBound means to you personally?

Lindblom: Sure. In my opinion, I don’t feel there are a lot of games out there that could be called cult classics. I’m really proud to have been involved with a game that was kind of low-key and gained popularity — or notoriety depending on how you want to look at it — over the years.

It’s a good feeling because I’m not young anymore. I’m 50. I actually got started in the industry fairly late. At this point in my career, I’ve worked on lots of games, many of which are very forgettable. So to have a game that was so personal for me and also a game that I worked really hard on, to have it gain a following over time and have people respond favorably to it is really a satisfying life experience that not a lot of people get.

I mean there’s a video I found where somebody emulated the game and hacked some of the text to propose to their girlfriend. I saw that and I just thought wow, because they’re obviously huge fans and the game obviously meant something to them. It’s hugely satisfying to know I played a part in that.

Wired: What would you say to those experiencing EarthBound for the first time?

Lindblom: It’s a game that’s meant to be played all the way through. There are times when I think our modern life is pretty cynical and it’s an existence in which it’s easy to forget about the good things.

I think if you approach EarthBound with an open mind, you’ll find that it’s really a glass half full kind of game. That was the way I wrote it and that was the way I wanted people to take it. It’s meant to be a positive thing about always progressing, always getting better, always moving forward towards an ultimate goal. Which, happens to be saving the world in this case.

But I really hope people go into it with an open, easygoing attitude and don’t try to prove wrong the 18 years of hype they may have been subjected to. We were at a pretty early point in game development, but I think it’s a good game that’s aged well.